The hole in the road was so big and so deep that some said faeries,…

The beauty is that we produce the coffee: Exploring manual brewing’s popularity in Indonesia

Article has been published in Perfect Daily Grind

Although Indonesia has long since been one of the world’s leading coffee producers, its coffee shop culture is comparatively young. Domestic consumption has quadrupled in the country in the last 30 years; today, this mainly takes the form of sweetened, lower-quality coffee beverages sold by street vendors, such as es kopi susu.

However, an increasing interest in coffee led by younger generations and Indonesia’s growing middle class means consumption is on the rise. This has led to the emergence of specialty coffee shops across the country.

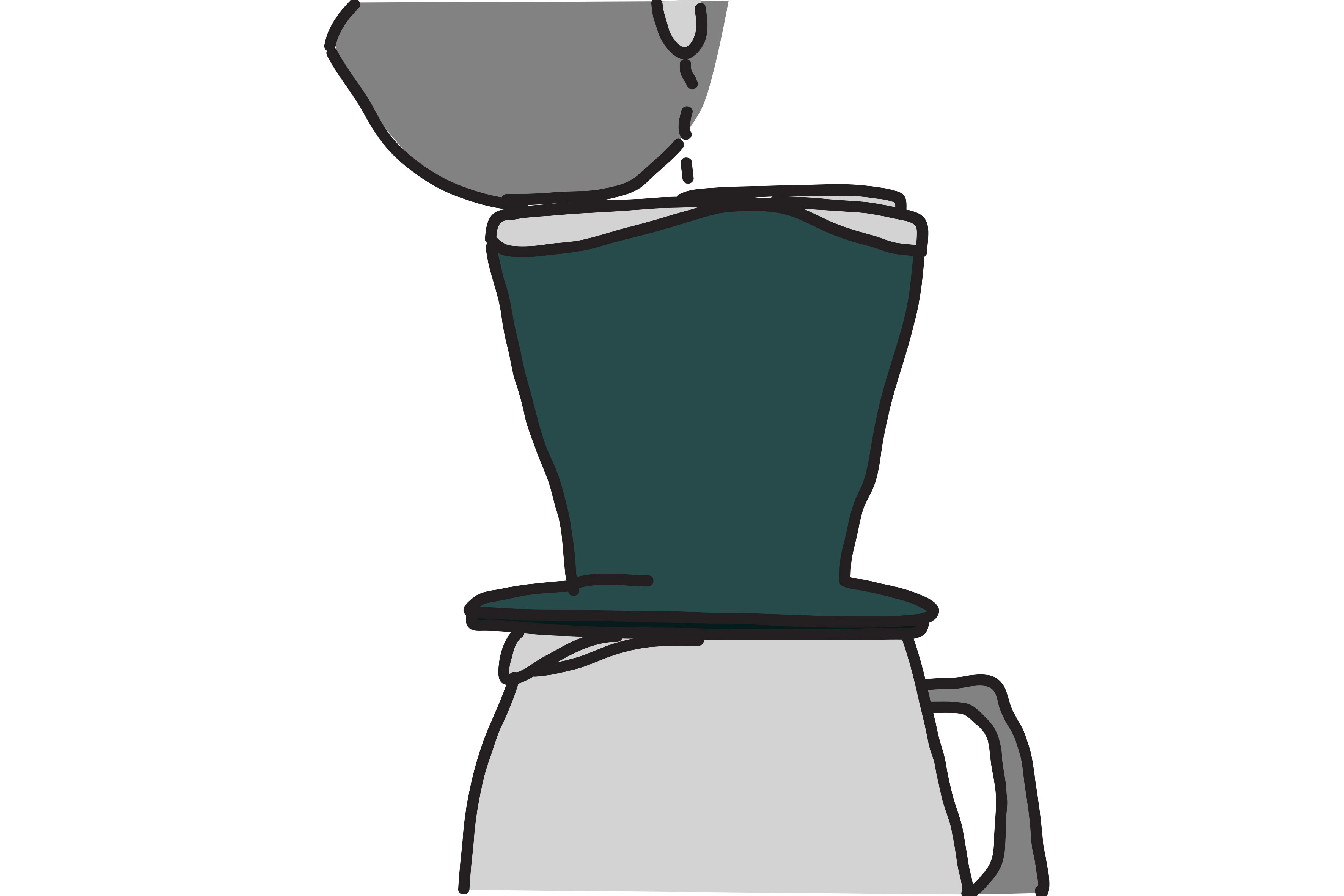

As such, manual brewing methods, a common fixture of specialty coffee culture, have started to become more popular in Indonesia. Affordable and accessible, they are changing the way Indonesians view their most valuable agricultural export, and bringing good coffee to more people than ever before.

To find out more about manual brewing in Indonesia, I spoke with two coffee experts from the country. Read on to find out what they said.

WHY HAS MANUAL BREWING BECOME SO POPULAR IN INDONESIA?

Indonesia is the world’s fourth-largest coffee producer by volume. Most of the coffee grown in the country has historically been exported, with common destinations including the US, Japan, and Italy.

However, in recent years, a greater appreciation for specialty coffee has emerged among the country’s younger generations and a growing middle class. As such, domestic consumption (including of Indonesian-grown coffee) has grown.

This has been helped in part by a thriving manual brewing scene across Indonesia, from Bali to Jakarta. Moka pots and pour over drippers have become a familiar sight for many of the country’s 270 million inhabitants.

One of the reasons that manual brewing (rather than espresso) has become so popular in Indonesia is the fact that it has relatively low operational costs for coffee shop owners.

Historically, Indonesian coffee consumption has been dominated by instant coffee thanks to its affordability and convenience. And even when higher quality coffee and espresso-based beverages were consumed, they were largely left to chains such as Starbucks, which opened the first of more than 300 Indonesian stores in Jakarta in 2002.

However, the cost-effective nature of most manual brewing equipment has allowed smaller, independent coffee shops to establish themselves in Indonesia’s growing specialty coffee scene.

Pepeng is one of the owners of Klinik Kopi, a popular coffee shop in the city of Yogyakarta, Java. He tells me that what first attracted him to manual brewing was its simplicity.

“Manual brewing is simple and practical,” he tells me. “I don’t need to think about milk that will go stale, nor do I have to think about the cost of the electricity, or the investment I’d have made [in an] espresso machine.”

Pepeng’s coffee shop style is compact and smart, with no unnecessary frills. It’s an approach reminiscent of the minimalist, played-down specialty coffee shops one might find in Scandinavia or Japan. This kind of identity is common, Pepeng says, to specialty coffee shops elsewhere in Indonesia.

Furthermore, even though espresso-based beverages remain popular among specialty coffee consumers, the initial outlay of an espresso machine is a risky investment. In comparison, the affordable market entry that manual brewing methods offer has allowed Indonesia’s specialty coffee culture to develop and grow.

Pepeng explains that the low cost of manual brewing equipment helps him to manage his finances more effectively. This has been particularly important during the Covid-19 pandemic.

“Manual brewing is simple and practical,” he tells me. “I don’t need to think about milk that will go stale, nor do I have to think about the cost of the electricity, or the investment I’d have made [in an] espresso machine.”

“Despite the closure of businesses in Yogyakarta due to the pandemic, I’ve been able to survive and make up revenue as restrictions have been gradually lifted,” he says.

Pepeng adds that in 2017, he partnered with a local ceramic artisan to design his own dripper. This, he says, is called the “koka”.

“It started because I want to be able to use different kinds of paper filter for one dripper,” Pepeng tells me. “So, if I want to make a cleaner cup, I’ll use V60 paper. For medium light coffee, I’ll use a flat bottom dripper filter. If I want to make a more intense coffee, I’ll use the kind of filter you’d use with a Kalita Wave.”

For Pepeng, the koka dripper represents the flexibility that is characteristic of manual brewing: “It has a lot of potential because it’s easily adapted by small businesses,” he says.

Read too: No Word After Taste.

FROM SUMATRA TO SULAWESI: THE DIVERSITY OF INDONESIAN COFFEE

Today, Indonesian coffee farms cover a total area of more than 1.2 million hectares, with some 930,000 of those used for robusta production.

Over 90% of the country’s farmers are smallholders. The diverse range of microclimates across the country’s 1.9 million square kilometres of land mean that the cup profiles vary massively from island to island.

In part, a range of locally-produced single origin coffees has been a factor in the growth of the country’s specialty coffee scene. For many Indonesian consumers, the initial desire to try specialty coffee is fuelled by a curiosity to understand and enjoy local coffees.

With manual brewing, locally-sourced coffee is readily available and customers have the opportunity to experience different coffees from different growing regions in the country.

Ryo Saputra Limijaya works in marketing in the Indonesian coffee sector. He says that the broad selection of single origins on offer keeps people interested in consuming domestically-produced coffee.

“Anomali Coffee was Indonesia’s first coffee shop and has sold 100% Indonesian beans since 2007,” he explains. “They can sell between nine and eleven single origins at a time, from Java and Sumatra to Toraja and Bali.”

The diversity on offer means that coffee shop owners can afford to rely less on imports, instead focusing on attaining specialty-grade coffee from local smallholder farmers.

Pepeng tells me that while there’s growing interest in African coffees, 90% of his customers come to Klinik Kopi to try Indonesian single origins. Some prefer the chocolate notes often found in coffee from Toraja, while others may opt for the refreshing fruity notes typical of Balinese coffee.

However, the majority of coffee produced in Indonesia is robusta. As a result, consumers often question the quality of local beans when coffee shops claim they are specialty-grade.

The diversity on offer means that coffee shop owners can afford to rely less on imports, instead focusing on attaining specialty-grade coffee from local smallholder farmers.

To differentiate himself and assure customers of his coffees’ quality, Pepeng says that he doesn’t rely on the traditional cup scoring system to source his beans. Instead, he says he works directly with local farmers to improve processing methods.

“As long as it’s processed well, tastes good, and I like it, then I’ll buy the coffee,” he tells me.

“For example, one coffee farmer I work with uses natural processing to produce a sweet, aromatic tobacco and lemongrass-ginger finish, without any over-fermented flavour notes. This complexity is more important to me than grading.”

In contrast, Ryo says that Anomali Coffee exclusively offers specialty-grade coffee (those with a cupping score of above 80 points). He adds that many Indonesians have high expectations for the coffee they drink, which has driven a general rise in quality.

“Many Indonesians who returned from time spent abroad have shown a strong interest in coffee and have brought new knowledge to the sector,” he says. “That’s why the quality of green coffee is increasing and learning about coffee has become more important. Over the past five years, it really feels like we’ve been growing exponentially.”

THE FUTURE OF MANUAL BREWING IN INDONESIA

Despite a rise in manual brewing among coffee shop owners in Indonesia, the market remains as diverse as the coffee it produces.

While manual brewing has gained momentum in recent years, Ryo tells me that each region has its own unique traditions when it comes to coffee consumption.

“The beauty is that we produce the coffee,” he says. “This, combined with the rich diversity that defines our coffee, means that no two regions are the same when it comes to consumption.

“Specialty coffee is booming in Aceh, but it won’t replace kopi tarik (coffee roasted with margarine and sugar). Similarly, in Makassar, kopi tiam (traditional drinks stalls) won’t disappear.

“Even though we promote specialty beans, if a customer wants us to brew it as tubruk (a traditional Indonesian beverage similar to Turkish coffee), we will do so.”

Read too: Belajar Nyeduh di Rumah Tahan.

As more young people return from studying abroad and bring their coffee habits with them, it’s clear that domestic coffee consumption in Indonesia will continue to evolve. While sweetened kopi beverages from street kiosks remain commonplace, we are now seeing an increasing number of consumers demanding specialty coffee.

At the heart of this change is Indonesia’s manual brewing scene. It has helped many coffee shop owners enter the market, where they have been able to offer higher quality coffee to millions. As interest in Indonesia as an origin grows both domestically and internationally, this trend shows no sign of slowing down.

Perfect Daily Grind

Photo credits: Klinik Kopi and Anomali Coffee

Writter : Michelle Anindya